When did my obsession with time travel first begin?

Was it when I made my first real mistake? This is one of the classic fixations of the time travel narrative, after all — the idea that if you could just go back and make another choice, your life would be totally different. Better, even.

Of all time travel movies, I’ve probably read the most about Donnie Darko (a coming-of-age cult classic starring Jake Gyllenhaal and a terrifying bunny rabbit) and Primer (a cerebral Sundance hit made on a $7,000 budget). I remember being totally enthralled by my first viewings of each film. When the credits rolled, I knew I didn’t want to say goodbye just yet — I wanted to keep living in those stories.

And so I turned to perhaps the #1 resource of my adolescent cinematic education: the IMDb message boards.

The Internet Movie Database got its start on a fan-run Usenet database group back in 1990. These days it’s a reliable online resource for information like casting and release dates, usually present in the first few results for any film’s Google search. If you’ve ever thought “Hey, it’s that guy!” when someone walks onscreen and proceeded to look up his credits online, you probably used IMDb.

Until 2017, IMDb was my go-to after watching a movie for one reason: every film had its own dedicated message board. This meant there was a centralized discussion hub for every single movie I saw, and it was accessible to anyone who cared enough to run a cursory online search for the film after viewing. If you had a hyper-specific question or the desire to analyze some minute detail, chances were someone on the board shared your interest. And because discussion was centralized around individual films, you could scan that board’s topics in a few minutes and find them. As this New Statesman piece recalls, you could post your “small weird questions” and “someone would always answer.” Sometimes even years later.

Back then, the IMDb message boards offered a place that I could turn to in order to understand a film I really loved through the perspectives of other people.

You can probably guess where this is going. On February 20th, 2017, IMDb shuttered the boards for good, stating,

We considered many options to preserve the current message boards during our extensive review, but in the end concluded that they no longer provide a positive, useful experience for the vast majority of our more than 250 million monthly users worldwide.

At this point, I’ve watched so many websites come and go over the years that the cycle of digital farewells feels baked into my identity. And so, when another one of my internet homes closed its doors, I experienced a familiar sense of loss — but this one stung a bit more than the others.

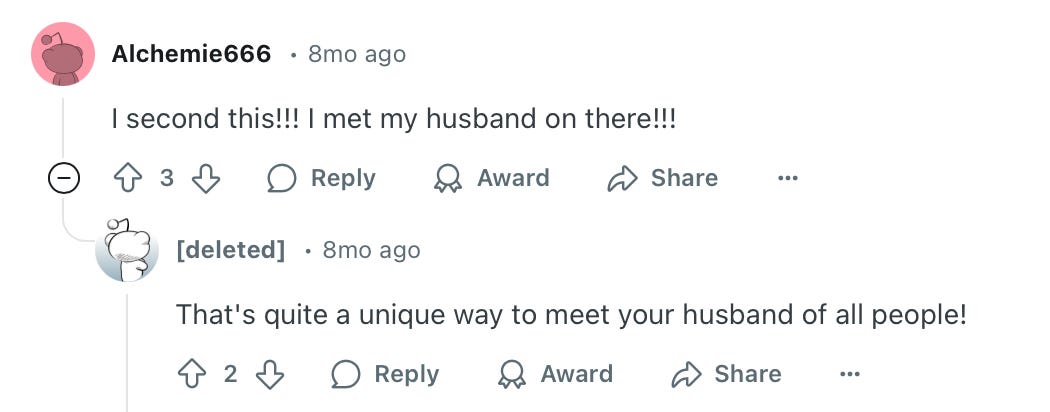

After the IMDb message boards closed, nothing else ever quite took their place for me. Nowadays Filmboards houses the archives, which are still active — though missing the centralized accessibility that IMDb maintains as one of the most visited sites on the internet (#48 globally as of April 2025). Letterboxd is a beloved resource for cinephiles, but serves a distinctly different purpose, tailored for reviews rather than discussion. Reddit offers a venue for more in-depth conversation, but lacks the comprehensiveness the boards offered; it can be harder to dig up conversation on lesser-known films. To say nothing, of course, of the advent of likes, upvotes, and algorithms, which alter the presentation of information, as well as the epidemic of trolls and bots.

At the end of the day, I miss having a home for those “small weird questions.” It was as if the boards contained a room for every movie — an ongoing conversation, just waiting for you to join — and the only key for entry was having seen the film. I’ve been trying to describe the online shift away from this feeling for years; in a short story I wrote exploring what it’d be like to find your doppelganger on the internet, I made this comparison:

As time passed, I began to feel more like the internet had become a gigantic stadium with no partitions at all. Nothing separating us any longer. Everyone screaming at once. But back then the internet felt to me like an infinite series of small doors we were all walking in and out of, and once in a great while you might cross paths with the person who would change your life.

I’ve read so much about internet nostalgia in the last few years. The question these narratives (and their critiques) often prompt is “Do we truly miss the past? Or do we miss who we were within it — younger, more hopeful, maybe a bit naïve.” And I’ll admit that for me, it’s probably a little of both. But more recently, I’ve been wondering why this 2017 message board closure felt like a personal turning point for how I experienced the internet. What happened? What’s different now?

Here’s what I realized: I still love the internet. But the way I use it has changed.

One of my biggest personal heartbreaks of our digital present is the deterioration of search engines. I count myself lucky to have come of age in a moment when answers were often just a few keyboard taps away, but it’s harder to find those answers than it used to be. It’s also worth noting that Facebook first introduced their algorithmic feed in 2009, with Twitter and Instagram following suit in 2016 — a year before the boards closed. The internet embraced algorithmic feeds over the course of the 2010s, triggering dramatic shifts in how information is shared today. The search has more obstacles now.

My fondest internet memories begin with the desire to search. Digging through archives, paging through blogs, clicking hyperlinks till I had a gallery of tabs. Looking back, I was never bothered by the absence of upvotes or a recommendation algorithm; when I went searching, my personal interests were what distinguished information and made it valuable. It was satisfying to assign that value myself through research across resources and mediums, rather than relying on a single platform’s mechanisms to direct my attention. I didn’t always find what I was looking for, but sometimes I found something even better.

I’ve realized that I don’t want an algorithm to guess at what I want to see and serve up those approximations to me. Nor am I particularly interested in efficiency or summaries. For me that’s never been where the interesting stuff lies. I want the tangents and the footnotes and the rabbit holes. I want to go looking on my own and see what I find.

I’m coming to understand that it’s the search itself that brings me joy — that deeply personal process of parsing information, moving through varied opinions, and assigning value before coming to my own conclusion. The same impulse motivates the writing of these essays, in fact — the journey educates and surprises and makes the conclusion possible. Often the place I end up is quite different than where I expected to be when I began. Over the last few years I have written myself into acceptance and understanding, epiphany and wonder. This is not an essay about AI, but I’m sure you can see what I’m getting at. I simply would not be the person I am or know the things about myself that I do without the desire to search and then write about it.

As I was gearing up to delete my Facebook and Twitter accounts recently, I found myself reminiscing about the IMDb message boards again. Of course, I don’t want to claim the boards were perfect, or hold them up as some sort of digital utopia. Lack of moderation had become a more significant problem in later years. Trolls and harassment aren’t new; they certainly existed then.

I think what I miss most is the seeming ubiquity of the impulse that led me to the boards. How instinctive that feeling used to be, the idea that others shared it, and the fact that this was a place for us. After 2017, feeds and algorithms increasingly pulled me away from that feeling. I found myself scrolling aimlessly instead of searching intentionally. Increasingly I turned to algorithmic feeds to kill time, resulting in passive slogs through a jumble of posts that often made me feel worse instead of better. And after a while, I started to miss that feeling of delight in discovery, using the internet first and foremost as a tool for exploration.

But I don’t have to return to the aughts to get back to it. Maybe the search can be a commitment, a creative practice. From now on, when I open a browser or pick up my phone, I want to begin by asking myself one question:

What am I looking for?

Microfascination exists because I wanted to explore ways of connecting with readers beyond social media feeds. Many writers have turned to the email newsletter as a form because it subverts the modern creep of algorithms. But Microfascination is also a personal practice in curiosity. In the inaugural issue back in November 2022, I quoted from Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing:

So why go down the rabbit hole? First and most basically, it is enjoyable. Curiosity, something we know most of all from childhood, is a forward-driving force that derives from the differential between what is known and not known. Even morbid curiosity assumes there is something you haven’t seen that you’d like to see, creating a kind of pleasant sensation of unfinished-ness and of something just around the corner. Although it’s never seemed like a choice to me, I live for this feeling. Curiosity is what gets me so involved in something that I forget myself.

I’m starting to think that I created Microfascination because of a subconscious need to cultivate my own curiosity. Suddenly I had a monthly assignment to offset the effect of the algorithmic feeds I’d been consuming for years, without much thought to their impact. I guess it really is just like I wrote back in January, when I took a closer look at the Werner Herzog penguin:

You can always figure out the why later on, as you go. Sometimes I think that discovery is where the real magic is.

Time travel movies often demonstrate that if you try to go back and “fix” one thing, you just end up creating a new problem. I understand the temptation to make generalizations like “The internet was a mistake,” or “Social media ruined the internet.” But it’s not quite that simple, is it? I am who I am because of the discoveries I’ve made here, the communities I’ve found — not to mention most of you came to this newsletter because of social media. It makes me sad to see so much division and anger online, but that doesn’t have to define our experience. Like with anything else, internet use should be directed by mindfulness and intentionality. Choosing what to opt out of, becoming more conscious of what you’re taking in.

At times our current moment can tend toward unpleasant surreality — politically, technologically, artistically — but what I come back to is my belief that an innate curiosity still exists inside each one of us. Whatever the headlines say, I know humanity has not lost the fundamental desire to learn and explore and connect. Maybe curiosity and care will take a little more practice than they used to, but they’re far from gone.

Interestingly, there’s a particular John Cage quote that popped up two or three times in different contexts while I was going about my life this month:

As you continue, which you will do, the way to proceed will become apparent.

What I know right now is that I’m going to keep searching, and I can’t wait to share what I find.

If you’re interested in exploring these ideas further, I’ve got a few bonus rabbit holes to share this month:

Short fiction! In addition to the short story I wrote about finding your doppelganger on the internet, I wrote another about a social media influencer who builds a career out of vanishing mysteriously.

A zine! Google searching might not be what it used to, but this zine provides a handy pocket reference for getting better results.

Nonfiction books! Heartily recommend Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention—and How to Think Deeply Again, Nicholas Carr’s Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart, Catherine Price’s How to Break Up with Your Phone: The 30-Day Digital Detox Plan, Cal Newport’s Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World, and Kyle Chayka’s Filterworld: How Algorithms Flattened Culture, which all influenced my thinking here. If you’ve read other books in this vein, please recommend!

Film writing! Bright Wall/Dark Room is my go-to resource for thoughtful writing about the relationship between movies and the business of being alive. When the credits roll but I find that I want to keep living in the story, this is where I go now.

Video essays! Tiffany Ferguson consistently creates smart and nuanced analysis of internet culture. Super recommend her video essay breaking down why social media feels so different than it used to.

Time travel! Today’s IMDb message board screenshots are courtesy of The Wayback Machine, a tool for internet time travel brought to you by the Internet Archive.

Thanks as always for reading! I’ll see y’all again in June.

While reading this, I could feel my heartrate slow into the zone that allows my brain to wonder about things and ask questions again -- not just scramble for solutions and fixes. That was really cool. How'd you do that?