Funny thing happened this month. The harder I tried to write about Sylvia Plath, the more I ended up writing about wrestlers instead! That ever happened to you?

Originally the plan was to focus on Plath’s unfinished (and mysteriously vanished) novel, Double Exposure. According to her own correspondence, this semi-autobiographical book followed “a wife whose husband turns out to be a deserter and philanderer.” Like The Bell Jar before it, this book clearly pulled from Plath’s personal life, as we know Ted Hughes left her for the translator Assia Wevill. Though specifics vary depending on which Hughes interview you read, it seems relatively certain that Plath wrote a significant portion of Double Exposure before her death — only for the manuscript to disappear.

Many theories circulate to this day: Hughes destroyed it, Plath’s mother stole it, the pages lie buried in an archive. We may never know the truth — which drives me nuts, of course. But even if this unfinished draft was found, would we have the right to read it? Plath left no will, meaning the decisions about her writing fell to the man she had often been writing about. I pored over her diaries for years, but these days I wonder: Are any of us really entitled to the unfiltered truth of another person’s life? And what does it mean to search for truth in art, anyway?

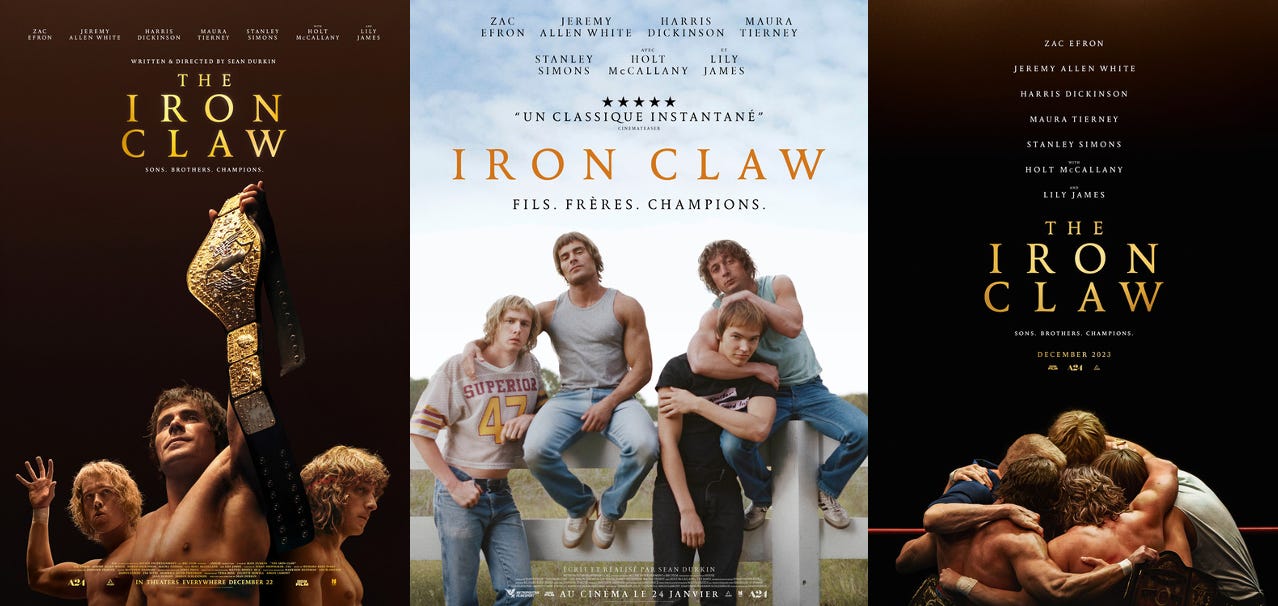

I’d already been turning these questions over in my head when I saw The Iron Claw earlier this month. Named one of 2023’s Top Ten Films by the National Board of Review, this biopic explores the legacy of the Von Erich brothers, their rise to prominence in the 1980s wrestling scene, and the mythical “curse” that whittled their family down over the years.

I love this movie so much that I’ve struggled to talk about it, which is the next tier of affection for me. I bypass the level where I can’t shut up about something and continue on to the one that renders me mute, unable to connect my feelings with words. I came out of the theater feeling less like I had watched a movie and more like something had happened to me. The best art feels like that — a turning point.

Sylvia came out twenty years prior, a biopic starring Gwyneth Paltrow released to mixed reviews. I was the target audience for this movie, although I didn’t see it until ten years later. Buried on my first laptop lies an earnest high school PowerPoint about “Daddy” that would probably be very unintentionally funny if I could track it down today. I read The Bell Jar at 15, combing the paperback shelves for a copy in my favorite used bookstore and eventually finding one with a stranger’s name written inside the front cover. These days Plath gets her own section on my shelf — The Collected Poems, The Unabridged Journals, Red Comet.

I watched Sylvia at the height of my Plath obsession. I was reading her diaries on a loop, only wanting to exist in a world where she was still alive. That year I spent most of my free time with a close friend who wrote a thesis on Plath; we were obsessed with mapping our lives onto hers, as if a famous writer could double as an astrological sign.

Watching a film knowing how it will end overlays every scene with dramatic tension. It was impossible to separate my knowledge of Plath’s death from the way Sylvia’s story unfurls, resulting in uncanny and relentless foreshadowing. In such cases, the interest lies not in how the story will end, but the manner in which the characters will arrive at that conclusion.

In The Iron Claw, Zac Efron’s Kevin explains early on that he believes his family is cursed, a dark haze that lingers with the viewer as a tragic history begins to reveal itself. In excavating a narrative from the Von Erichs’ real lives, the film explores a fictionalized idea of this curse, one which supposedly originated when Kevin’s father adopted his mother’s surname — as if a name is a kind of channel through which bad luck could now continue to flow. Kevin even reverts his newborn’s last name to Adkisson at a later point in the movie, hoping for a better future for his son.

As a form, the biopic imagines a reality where revelations of the future are buried in symbolic moments of the present. The viewer becomes a detective. It’s just as easy to comb through Plath’s writings and pick out all the words that foreshadow her death; Sylvia makes much of “Lady Lazarus” in particular:

I am only thirty.

And like the cat I have nine times to die.

Knowing that Plath took her own life at 30, the retrospective symbolism in her poetry is evident. But one can just as easily interpret the reverse:

Out of the ash

I rise with my red hair

How would we read those words today if she had lived?

Would life be better if you knew, concretely, that you could go back through everything you’d survived with a magnifying glass and use the past to predict your future? Or is there a freedom in imagining the alternative — that every new moment is a fresh collection of choices, lying entirely in the hands of the people who live them?

I’m reminded of the title of Plath’s lost book. Double Exposure references the photographic phenomenon in which film is twice bared to light, resulting in the appearance of multiple images within a single picture. Back in my photography days, I would imitate this analog technique in Photoshop, layering two things on top of each other to see what new meaning I could make. A girl closing her eyes to the camera might appear to be shutting out the world. But layered on top of a second image, a bird flying away from a power line — maybe she’s found freedom within.

An adaptation will always be a layer on top of the original story; it should never be mistaken for the truth. The final version of The Iron Claw’s screenplay omits the youngest Von Erich brother, Chris, from the family narrative; Meghan O’Rourke lamented that Sylvia “failed to explore the fact that Plath was one of the first major American poets to be a mother and to take the pleasure of motherhood as her subject.” The biopic begins at a disadvantage, as it’s fundamentally impossible to contain a life in a few hours. What falls to the cutting room floor might be left behind in favor of narrative flow or personal bias (and the exclusions don’t always honor the subject). But I’d like to think that there’s still something to be realized in the act of an honest attempt. New connections to be made, new meaning to uncover.

When we make art about real people, I don’t know that it’s possible to tell a complete story. I think we’re only ever projecting a fragment, inevitably steeped in our own perspective. But on the other hand, art is the best means we have of returning to the past in the present. It can be a way of keeping someone alive, even after they’re gone.

A wonderful song called “Live That Way Forever” plays over the ending credits of The Iron Claw. I’m hanging onto this feeling till they drag me away. I’ve learned that art can also be a way of suspending time. I wanna live that way forever. We can return to a world where Plath is still alive, writing her best work. We can celebrate the best of the Von Erich legacy — the moments they were together. These films preserve the joy alongside the sorrow, right where it was left. And in each created world there is the enduring promise of meaning to be found, if only we look closely enough.

Happy New Year! Go see The Iron Claw if it’s still playing near you. I’ll see y’all again in February!

Great observation about the viewer becoming a detective while watching a biopic. I may be quoting you on that in the future!

Love this. Definitely has me excited to check out "The Iron Claw"!!